Life Inside A Job

Lessons for early-career leaders choosing between impressive and sustainable

I want a restaurant

My friend Sam’s eyes lit up when he told me he wanted to quit his corporate job and open a restaurant. We were sitting in the diner we’d gone to for years, the kind of place where the waitress greets you by name and your coffee keeps getting topped off without you noticing it happen.

Sam wasn’t talking about rent or margins. He was talking about relief. He was talking about wanting a life where his effort connected to something real, where the day didn’t dissolve into meetings and decks and a manager’s mood.

He described the restaurant like he were already in it. A short fresh menu. Simple food done well. A small bar. A room with regulars. A place that felt like it belonged to the neighborhood.

I asked, “Who’s going to supply you?”

Sam paused, then said, “I’ll figure that out.” He wasn’t being defensive. He just hadn’t gotten into the invisible details yet.

That night, I didn’t push. I let him have the dream. Hell, I encouraged him. But the next week he texted me a photo. It was a lease listing. Real square footage. Real rent. Real.

“Thinking about it,” he wrote.

So I called him and said, “Before you sign anything, call three restaurant owners and request them to walk you through a normal day. Not their best day. Not the day the local paper shows up. A normal day.”

Sam did it. He’s that kind of person – curious, practical, willing to learn and unafraid to put in the work.

Two days later, he called me back and didn’t sound as lit up anymore.

He sounded awake and aware.

One owner had told him that if you own a restaurant, you don’t really get weekends; you get responsibilities that mostly happen to occur on weekends. Another told him staffing is the job, and that food is what people blame when staffing breaks down. The third said, “You’ll think you’re opening a restaurant. You’re opening a set of problems that show up daily, no matter how you feel.”

Sam had listened like a good student, taken notes, thanked them, and then called me.

“What are you thinking?” I asked.

He said, “I think I wanted the idea. I didn’t think about the details behind the idea.”

He still wanted it. But he wasn’t ready for it. Not yet. And this is where the first story turns into what it is.

Sam didn’t slow down and regroup. Sam panicked.

Two weeks later, he signed a lease with a partner he barely knew because the rent looked “too good to lose.” He bought equipment because it felt like progress. He hired staff before he had a system. He told his boss he was leaving before the permits were approved. He moved fast because moving fast made him feel that everything was coming together.

The restaurant opened late, because restaurants always open late, and Sam walked into his first Friday night like he was stepping into a dream that finally belonged to him.

By 9:30 p.m., the dream was gone.

The POS system froze. A cook didn’t show. The vendor's delivery that morning had been just slightly wrong. A table sent back a dish that Sam had tested three times at home and loved. His partner disappeared “to handle something” and did not return for the rest of the evening. Sam found himself in the kitchen, then the dining room, then on the phone, then back in the kitchen, trying to solve five problems at once while pretending none of them were happening.

When he called me past midnight, he sounded tired, stunned, and somewhat embarrassed.

He said, “I can’t feel my feet.”

The restaurant lasted eleven months.

Sam didn’t fail because he was foolish. He failed because he wanted something real badly and moved toward it the way high performers often move – fast, optimistic, sure they’ll figure it out on the fly – without first understanding what the work actually demanded of him day after day.

When he shut it down, he didn’t talk about money first. He talked about the emotional weight of being needed all the time. He talked about waking up already behind. He talked about how every “small issue” had a way of turning into a multi-day fix.

He said, “I loved the idea of it. I didn’t love the way it ran my life.”

Sam wanted to own a restaurant, and he got it – without understanding what every day looks like when you own a restaurant, and learned the hard way that he did not want those types of days.

Eyes wide open

I ran into Maya at a coffee shop near her office. She was early in her career and had one of those jobs people talk about like it’s a trophy: investment banking. She had acquired the brand name. The salary. The social proof. The kind of role that makes families relax, because now they can say, “She’s set.”

Maya’s mom would glow with pride when she told everyone where her daughter worked.

Maya looked sharp and engaged.

We talked for a while and she told me something that surprised me. Not about the work being hard – everyone knows it’s hard – but about how she had come to understand what she was actually signing up for.

She said, “I did a ton of research before I started. I needed to know what it would actually be like.”

She didn’t mean she read a description online. She meant she met with people who were already doing the job and asked them for specifics. What time do you get in? What do you do first? What happens at night? What repeats every week? What parts make you feel proud? What part makes you feel dead inside? What do you spend hours doing that no one outside the job would guess?

Maya told me one associate had told her, “Most of this job,” he said, “is making someone else’s thinking look clean.”

Another told her, “Sometimes we just sleep in the office to keep up with frequent updates to pitch decks and rush home for a change and shower and then rush right back.”

That didn’t scare her. It clarified what she was signing up for.

She said, “I realized I wasn’t chasing ‘finance.’ I was choosing intensity. I was choosing a steep learning curve. I was choosing a place where the standards are brutal, and you get better fast, and where a lot of your early work is invisible.”

Then she said the most important part, “I also realized I’m the kind of person who can do that for a few years without hating myself.”

That’s a powerful insight into who you are. That’s an informed commitment.

Maya wasn’t a romantic about it. She didn’t pretend it was healthy. She simply knew what her days would contain, and she decided, eyes open, that the trade was worth it for now.

Maya chose a demanding path after doing the work to understand it, and decided it was what she wanted to sign up for.

Impact

Lina is the kind of early-career leader who wanted her work to mean something, and she doesn’t use “meaning” as a brand. She genuinely wants her hours pointed at something she can feel good about every week.

Lina used to work on one of my corporate teams. One day, she knocked on my office door and announced with a bright smile that she’d accepted a job at a mission-driven organization. I could see the pride and conviction on her face. The mission was real. The people were good. The work mattered.

Six months in, she called me on a Tuesday afternoon and asked if I could meet for a coffee.

She said, “I feel like I’m failing, but I can’t tell if I’m failing at the job or failing at wanting it.”

I have always admired Lina’s direct honesty.

It’s something a lot of early-career people would be afraid to say, because it sounds like weakness when it’s actually clarity trying to break through.

Lina walked me through her days. Fundraising pressure. Stakeholder expectations. Internal politics, even though everyone technically wanted the same outcome. The emotional load of working around real suffering. The constant need to explain complexity to people who just wanted simple stories.

She wasn’t disappointed in the mission. She was tired of the daily friction.

After our meeting, she decided to do something that most people don’t do because it takes humility, courage, and time.

She started interviewing people in adjacent roles, not for a job, but to understand where there might be an opportunity to have a different kind of day. She spoke to someone in program operations. Someone in analytics. Someone in partnerships. Someone in product at a healthcare company. She asked them to describe their week in detail, what they did when things went well, what they did when things went badly, what kinds of decisions they made, and what kinds of problems kept showing up.

She had told me, “I realized I don’t mind hard work. I mind the kind of hard work that leaves me emotionally wrung out every day.”

She didn’t quit the mission. She recommitted to it in a different form.

Lina shifted into an operational role where her days were still demanding, but the demands fit her better. More building. More systems. More clear outcomes. Less constant persuasion. Less emotional baggage.

Lina did the work to understand what the job is like, and chose something different –not because the first path was bad, but because the daily reality didn’t fit.

So what

Sam, Maya, and Lina ended up in different places.

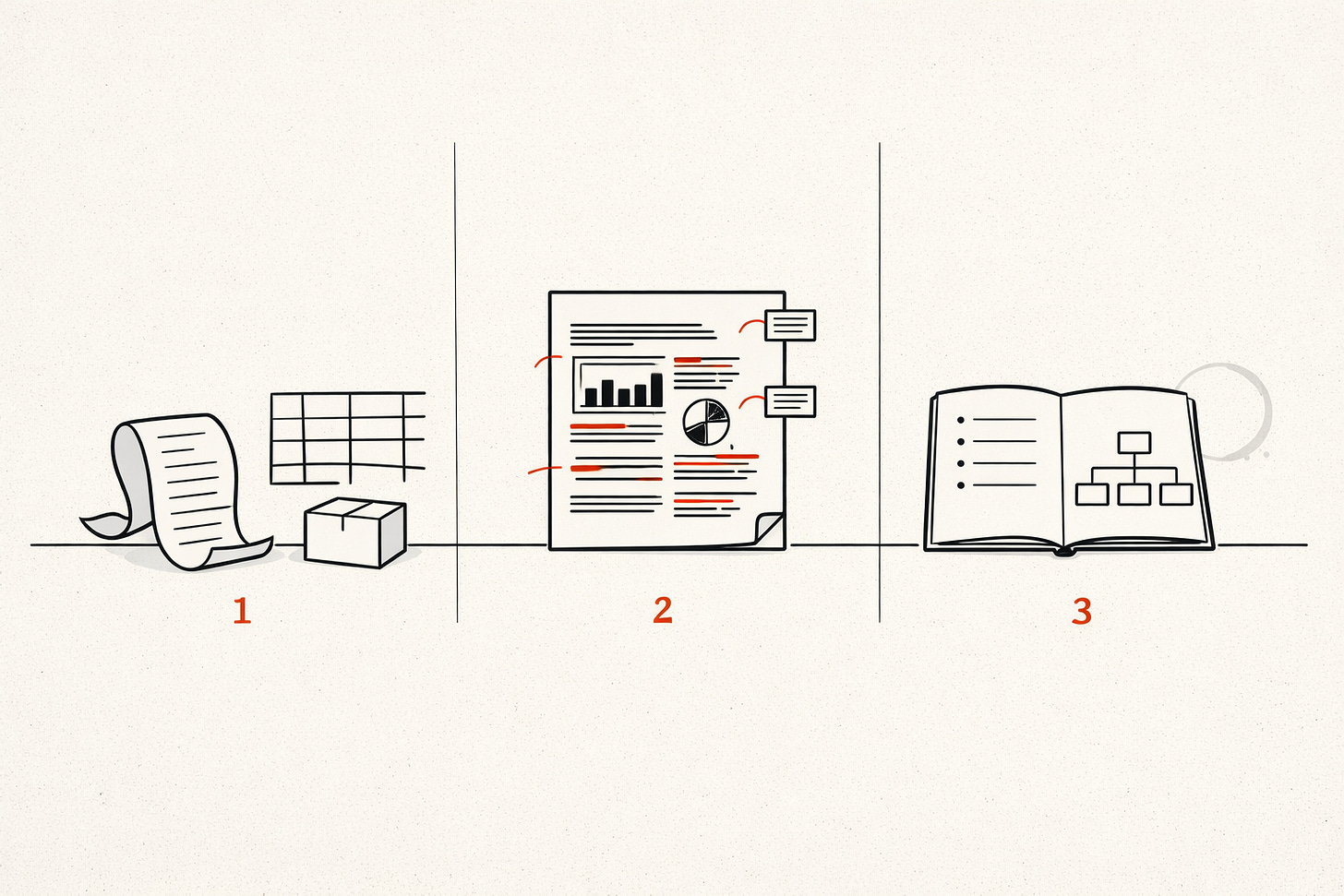

Sam wanted something without understanding the daily machine, and he paid for the lesson in time, real money, and unimaginable exhaustion. Maya did the work to understand the days her work would entail and chose the intensity with intention. Lina did the work to understand the kind of work it takes to make an impact and chose something different that was hard but empowering for her.

If you take anything from these three stories, let it be this: don’t only ask, “Is this a good job?” Ask, “What does the actual work look like? What are the specific routines, tasks, and can I see myself soing the work and thriving?”

Be honest.

And remember - honesty, especially to ourselves, is an unfair advantage.

Thank you for reading and spending some of your day with me.

Adi

great read! As someone with their first job I empathize: it's very hard to visualize yourself in a "long term" position as all the experiences leading up to a job (internships, college) have been temporary and meant to "lead to something"