Curiosity Without Performance

When I stopped pretending to know

TL;DR: For years, I thought leadership meant having answers. Then one afternoon, a young analyst quietly questioned my plan. Instead of defending it, I said, “I might have missed that.” Later that night, while I was helping my son with a science project, he said, “Can we just figure it out together?” We did – and in that moment, I realized how much I’d forgotten the joy of not knowing. Curiosity, I have learned, doesn’t weaken authority; it deepens trust. When we stop performing and start listening, we lead better. Sometimes the strongest thing you can say is the most human: I don’t know yet, but let’s find out together.

And now the essay.

It was late in the afternoon when I first noticed how loud my certainty had become.

The room was still, except for the faint hum of the projector and the rhythm of people shifting in their chairs. Someone from the team was walking through a presentation I had already half-read that morning, a plan we had built carefully, defended loudly, and believed in completely. I should have been paying attention, but my mind kept replaying the small line in an email I had ignored earlier that week – one of the analysts questioning one of our assumptions. The note had been polite, even hesitant, the kind of message you send when you know you’re right but are afraid to sound like it. I had skimmed it, nodded, and moved on. After all, we had deadlines, and the model had already been reviewed twice.

Now, as he spoke up in the meeting, pointing to the same error, I saw it clearly – a small, almost invisible mistake, the kind that doesn’t derail the big plan, but reminds you how thin the line is between knowing and assuming. The room went quiet. Thirty people, waiting for me to speak. I felt that familiar tightening in my chest, the one that comes from years of being the person who is supposed to know. I had built my career on that – being composed, informed, decisive. It was part of the job, and also, if I am honest, part of my identity.

I was the one who steadied the table.

But in that moment, something in me hesitated. I looked at the chart again and felt a wave of humility that surprised me. I could feel the words forming – the usual ones, the ones that explain and reassure – and I let them go. What came out instead was quieter, slower.

“I might have missed that,” I said.

A few heads lifted. No one spoke. The silence wasn’t uncomfortable this time; it felt alive, like the air in the room had changed. We looked again at the data, and for the first time that week, the conversation stopped being about who was right. We were just trying to understand.

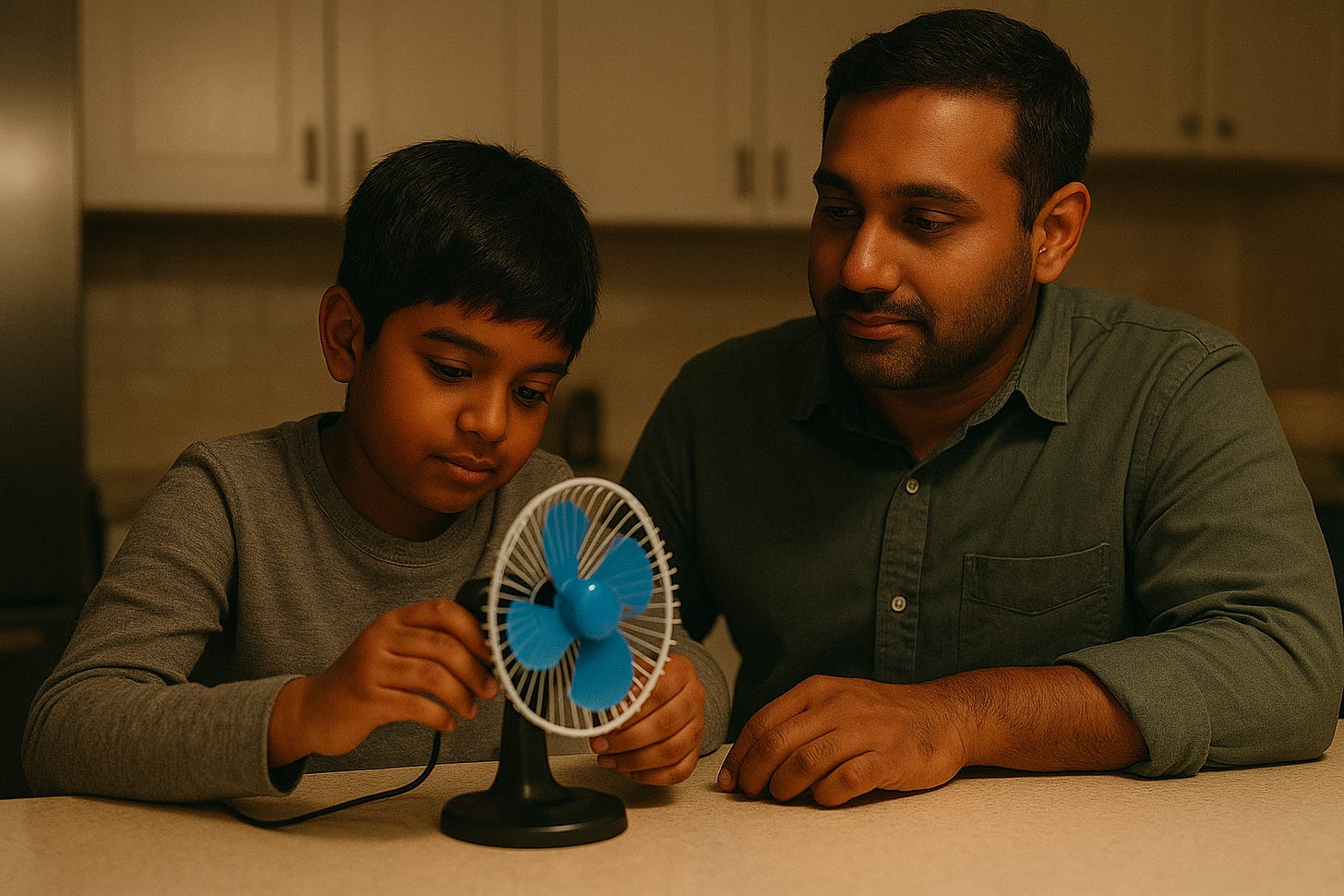

That night, I came home later than usual. My son was sitting at the kitchen counter surrounded by a mess of wires, batteries, and tape. He was building a science project – something that was supposed to make a paper fan spin. He looked frustrated, eyebrows scrunched, jaw tight in the same way mine must have looked that afternoon. When he saw me, he said, “I can’t get it to work. You know how to do this stuff, right?”

I wanted to help.

I started explaining circuits and connections, trying to sound confident. Halfway through, he stopped me. “Can we just figure it out together?” he said, and his voice was so simple, so open, that it disarmed me completely.

We sat side by side, trying things that didn’t work, breaking the tape, fixing it again. At one point, the fan trembled, then began to spin slowly, and his face lit up. He didn’t even look at me – he just watched the motion, the small miracle of it, as if the world had just said yes.

I found myself watching him instead, realizing how long it had been since I’d learned something with that kind of wonder.

When you spend enough years leading, you start to mistake performance for presence. You forget what it feels like to be curious without the pressure to teach. I had spent so much of my life filling silence with knowledge, when what I needed most was to return to the quiet where questions begin. That night, in the soft light of the kitchen, I realized how much of leadership is really about unlearning — letting go of the armor of knowing so that real connection can get through.

The next morning, I sent the analyst a note. No preamble. Just: “You were right about that model. Thank you for catching it.” He replied a few hours later, “Thanks for saying that. I wasn’t sure if I should have spoken up.” It was a short exchange, but it lingered with me all day. I thought about how many times I must have been that young – seeing something clearly, doubting myself enough to stay quiet – and how easily we lose that voice when certainty becomes a habit.

Over the next few weeks, I noticed small shifts. People started asking more questions, sharing doubts earlier, laughing a little more in meetings. The pace didn’t slow down; it just became more human and warm. And I learned that when you make room for curiosity, you don’t lose authority – you gain trust.

A few days later, my son showed me the finished project. The fan spun fast and steady this time, and he grinned the way only a child can when they’ve solved something through persistence, not perfection.

He said, “See? We just had to keep trying.” I nodded, not because I had to provide an answer, but because I finally understood the question.

I still have days when the old rhythm returns, when silence feels like weakness, and I reach for the comfort of being right. But every time I think of that meeting and that small motor on the kitchen counter, I remember what it means to lead without performing. The truth is, not knowing doesn’t make you smaller. It makes you real.

And that is where learning begins.

Enjoy your loved ones and the rest of your Sunday!

And thank you for spending some of it with me.

Warm regards,

Adi

I love the insight of your post and I’d like to learn more about writing and staying consistent even in tough times. You make it seem so easy to write and I’m curious about how you can navigate this so freely.

It's very interesting to motivate guide Yr son by listening stay hold with him nice