Casey's Story

You cut a role. Then you learn what that person really did.

Prologue: After I Left

I’ve hired people who didn’t just take a job – they reorganized their whole lives around it. I’ve watched them grow into leaders, watched them build things that held under pressure, watched them learn how to care about customers without becoming brittle or cynical. I’ve stood in the middle of teams that were finally working the way teams are supposed to work: clear decisions, honest handoffs, disagreements that stayed respectful, the quiet pride of people who knew they were building something real.

And then I left.

No drama, no scandal – just the normal churn of modern leadership: contract done, CEO churn, new mandate, a new role, a new problem set, a polite farewell, a promise to keep in touch…

What happened next was so familiar – I almost expected it. The teams I built got rationalized, simplified, and optimized. And because the decision makers were in a hurry, the cuts came without a lot of thought.

The pain showed up exactly where it always does. Customers felt it first: support queues slowed down and then stopped moving, fixes started taking three sprints instead of one afternoon, and incidents that used to be contained quietly turned into public scars. Then the company felt it: platforms got brittle, products lost their pulse, profits started to sag. But the people – my people, the ones I’d recruited and defended and trusted with hard work – paid the heaviest price, because for the ones making the decisions, they were just numbers.

This is a story about one of them.

Rooms Where Decisions Get Made

The boardroom didn’t feel tense so much as deliberately calm, the kind of calm that comes from everyone agreeing.

The windows ran floor to ceiling, and beyond them, the city looked unbothered, full of commuters and cranes and traffic lights doing their work without opinion. The table was long, and in the middle sat the small, polite offerings of corporate care – coffee, water, a bowl of mints – things that made the room look hospitable even when the agenda isn’t.

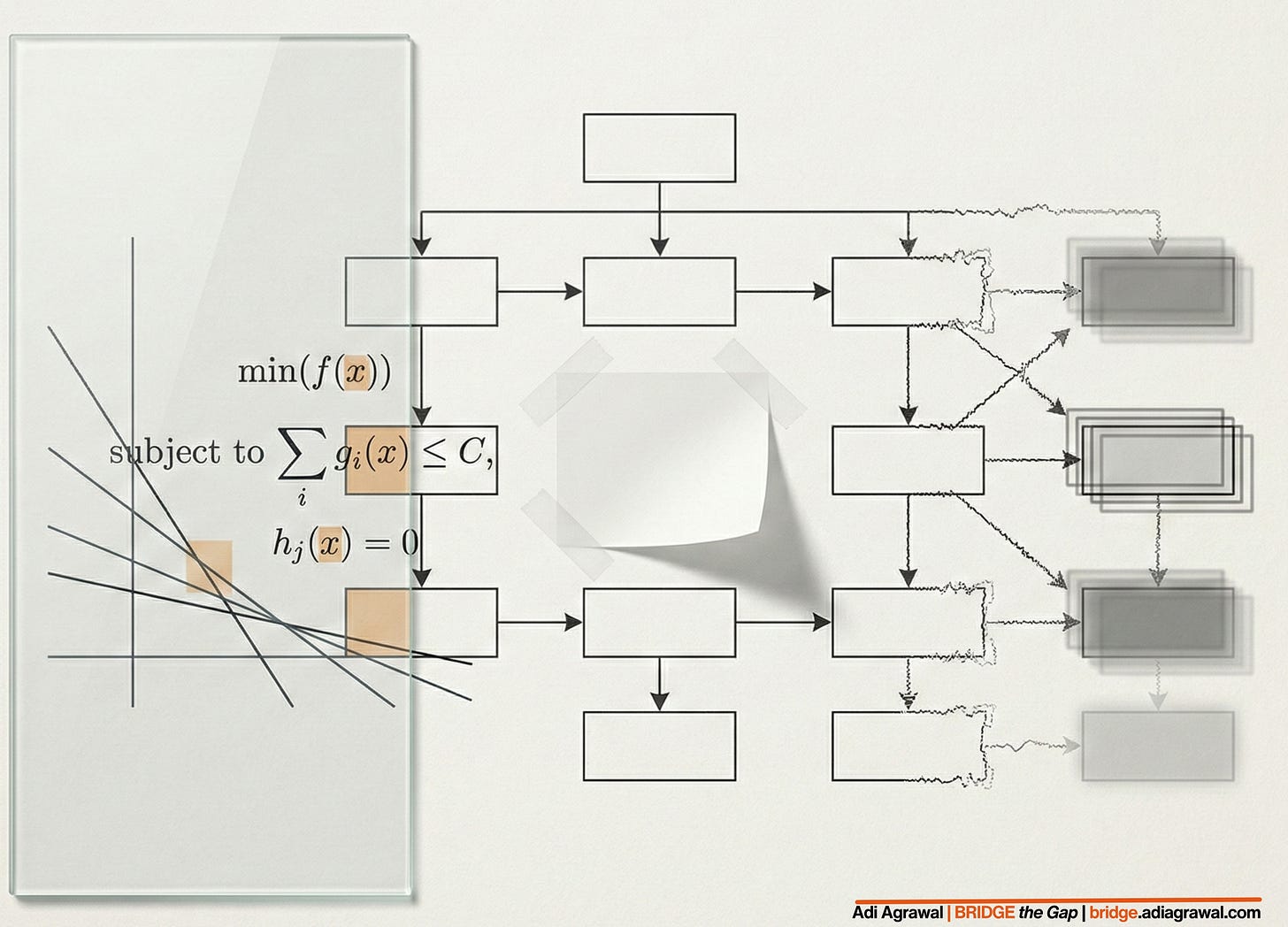

On the screen, a deck was already deep into its confident middle: charts that rose and fell with reassuring precision, tables with highlighted cells, a few bold labels that gave urgency to the tone of strategy.

They talked about “simplification” the way people talk about gravity, as if it were a neutral force and not a choice. Next was “margin improvement”.

The phrases kept emotion out of the air: run-rate savings, optimization, workforce rebalancing. There were no names, no faces, no mention of where people lived or how long it might take them to find a new job or how many children depended on their paycheck. There was just a tidy logic: here is the model, here are the targets, here is the timeline.

When someone asked what the plan would do to “execution,” the answer was a slide that promised resilience, a second slide that promised “coverage,” and then a third slide that implied the risk could be managed if everyone moved fast enough. Heads nodded in the soft rhythm of consensus.

In the notes section of the deck – small, gray, easy to overlook – was the closest thing to reality: a list of impacted roles, grouped by function.

One of those roles belonged to Casey.

Model Can’t See

Casey did not know his name was gone from the org chart. He was at his desk that morning, answering questions in a team channel, moving between a backlog and a customer escalation, doing the unglamorous work that kept the product alive in the hands of customers. He had a habit of absorbing chaos without spreading it, and the people around him relied on that more than they admitted.

Casey lived the kind of life that makes most corporate language feel vaguely ridiculous: a modest house in a quiet neighborhood outside a midsize city, two kids who argued about whose turn it was to pick the music in the car, a spouse who carried the invisible weight of planning and remembering and coordinating. His weekends were carpools and grocery runs and a backyard that never quite looked finished. His workdays were meetings and tradeoffs and the persistent, low-grade pressure of making decisions that mattered without having the authority to make them cleanly.

He was good at the job in the way the best people are good at the job: not with theatrics, not with self-promotion, but with steadiness. In meetings, he asked the question that forced people to stop telling themselves stories and accept the truth. He wrote notes afterward, not because it earned him anything, but because he couldn’t stand how often a team lost a week to a disagreement they’d already had and gotten past. He noticed when a feature was being built to satisfy internal pride instead of a real customer need, and he had the courage to say it plainly, without making enemies.

He also believed, in a quiet and stubborn way, that the system rewarded effort.

It wasn’t naïve so much as necessary. Most people can’t get through adult life without believing that reliability counts for something, that if you do what you said you’d do and show up when it’s hard, someone notices.

A few months earlier, that belief had helped him do something that felt like a milestone: he and his spouse bought their first home.

It wasn’t grand. It was chosen for practical reasons that felt, at the time, like a kind of victory: a payment they could manage, a school district they liked, and a reasonable commute. The house had a yard that needed work and a basement that promised possibility, and on their first evening there, the kids ran from room to room like the walls had been waiting for them.

Casey stood in the doorway of the kitchen and watched it, the noise and the movement and the ordinary joy, and felt something settle in his chest that he mistook for security.

By the time the layoff came, that feeling had already become part of the house, woven into routines – packing lunches, paying bills, signing permission slips.

Five-Minute Meeting

The invitation arrived the day before: a five-minute meeting titled “Quick Sync.” No agenda. No context. It appeared on his calendar like a sudden but subtle intrusion.

He clicked into the call on Thursday morning with a cup of coffee still warm beside him. His manager was already there, posture too upright, expression controlled in a way that made Casey’s stomach tighten before anyone spoke. An HR business partner sat in another square with a composed face and a sympathetic tone she could summon on command. A third square was dark.

His manager said Casey’s name, then hesitated before he continued. What followed was a script. Casey could feel the script in the pacing, in the careful order of statements designed to prevent questions from turning into claims.

It wasn’t about performance. It was a business decision. The organization was changing. Some roles were impacted.

There was a brief explanation of severance and benefits, a list of next steps delivered as if they were housekeeping, and then the part that made Casey’s hands go cold: access would end immediately, equipment would be collected, and conversations could happen later through a formal channel.

He tried to ask about his team. He asked who would pick up the work that was half-finished, the customer who was waiting, and the decisions that weren’t yet made. He asked, in a voice he didn’t recognize, if there was anything he could do, any other role, any chance to stay.

His manager looked down and said he was sorry. The HR partner said she understood how hard this was. Casey listened to those sentences and felt their emptiness, not because the people saying them were monsters, but because the structure of the moment didn’t allow it. The call wasn’t designed for grief; it was designed for a clean separation.

Then it ended.

The screen returned to his own face, slightly distorted by the camera, and for a moment he stayed frozen, waiting for someone to come back, to correct it, to add a human minute to what had just happened. Nobody came back on.

Silence

The quiet of the house pressed in around him. Somewhere upstairs, a door was half-open. A jacket was draped over a chair. A kid’s water bottle sat on the counter. The normal evidence of a life continued to exist as if nothing had changed, and that mismatch made the moment feel unreal.

He sat there long enough that his coffee cooled.

When he finally stood up, his legs felt unreliable. He walked to the sink and rinsed a mug that didn’t need rinsing. He checked his phone, then set it down, then picked it up again. He opened the banking app and stared at the numbers with the flat, analytical attention of someone trying not to panic: mortgage date, daycare draft, utilities, credit cards.

He texted his spouse, then erased the text, then typed again: “Can you call me when you can?”

When the call came, he didn’t give a speech. He said, quietly, “They let me go,” and felt his throat tighten around the word go as if it were a place he’d been pushed out of.

That night, after the kids were asleep, he sat at the kitchen table with his laptop open. He updated his résumé. He wrote messages to people he hadn’t spoken to in a year, careful not to sound desperate, careful not to sound angry, careful to sound employable. He scrolled job postings until the titles blurred and the requirements started to feel like accusations.

The hardest part wasn’t the work of applying. The hardest part was the silence that followed.

No Slack messages. No calendar invites. No quick questions from engineers. No status updates. No small proofs of relevance. The rhythm he’d lived inside for years stopped abruptly, and in the quiet that followed, he could hear, too clearly, the doubts that work usually kept at bay.

He woke early with his mind already running. He stayed up late because sleep felt like surrender. He found himself looking at his children during breakfast and calculating how long he could keep their lives unchanged.

Consequences

Inside the company, Casey’s absence showed up in places the decision models hadn’t captured.

A customer escalation that Casey would have intercepted early lingered too long and became louder. A decision that Casey would have documented dissolved into disagreement and rework. Two teams drifted into building overlapping solutions because no one was minding the seams. The product didn’t collapse dramatically; it frayed, thread by thread, until even people who didn’t know Casey’s name began to feel the drag.

A few leaders noticed and said nothing, because noticing is not the same as being allowed to stop it.

A few outliers noticed and couldn’t not act. One sent Casey a short message that didn’t pretend to fix anything, simply acknowledging what mattered: “I didn’t know. I’m sorry. You were important here.” Casey read it more than once, not because it changed his situation, but because it told him his work had been real to someone.

Another called him, not with advice, not with a networking pitch, but with the plain question that sounded almost unfamiliar in corporate life: “How are you doing?”

Casey paused. The honest answer was complicated, and it was easier to offer a simpler one, something upbeat and contained. But his voice betrayed him. He told the truth in fragments: he felt embarrassed, he felt scared, he couldn’t stop replaying the call, he kept wondering what he’d missed.

The person on the other end listened and then said, softly, “You didn’t miss anything. This wasn’t about you.”

After the call, Casey sat at the table again – same chair, same light, same house – and felt a kind of grief he hadn’t expected. Not just grief for the job, but grief for the belief that had made him loyal, that had made him think reliability was a shield.

The company called what happened change management. It scheduled meetings about trust. They hired consultants to diagnose execution. But the truth was already visible, in the teams, in the people who remained: they had watched how quickly someone could be erased, and they were learning what that meant for them.

Casey would find his way forward, because people usually do, not because it’s easy, but because life doesn’t pause long enough to let you fall apart completely. Some mornings, he would feel steady. Some afternoons, he would feel brittle. He would learn how to introduce himself without a company name attached. He would learn what it costs to keep your family calm while your own confidence is cracking.

And somewhere, in another boardroom, a leadership team is going over numbers that are supposed to fit a narrative for decisions already made.

Balance sheets don’t remember names.

People do.

Closing

Years later, long after the severance is spent and the access badges are returned, the company will still have its models, its targets, its decks full of certainty. It will still tell itself that the decisions were necessary, that the timing was unfortunate, that the math left no room.

But the math is never the whole story. It never was.

Economically sound decisions require moral attention, because the economics we are trying to protect are created – quietly, daily, imperfectly – by the people we are treating as movable parts. The work that looks “redundant” on a slide is often the work that keeps a customer from leaving, keeps an incident from spreading, keeps a team from arguing itself into paralysis, keeps a product alive in the hands of people who depend on it.

If you have to make cuts, make them with awareness and grace. Do the hard work of knowing what your people actually do, what they prevent, what they hold together, what they make possible. Learn their contributions before you erase their roles. Measure more than cost. Measure capability, continuity, trust—because those are not soft things. They are the hidden structure of performance.

Remember, it is people who make your economics possible.

When you forget that, the spreadsheet may still balance.

The business won’t.

Thank you for reading and spending some of your day with me.

My best wishes for an abundant, healthy, and joyful 2026 to your family and you.

Adi